Research Project

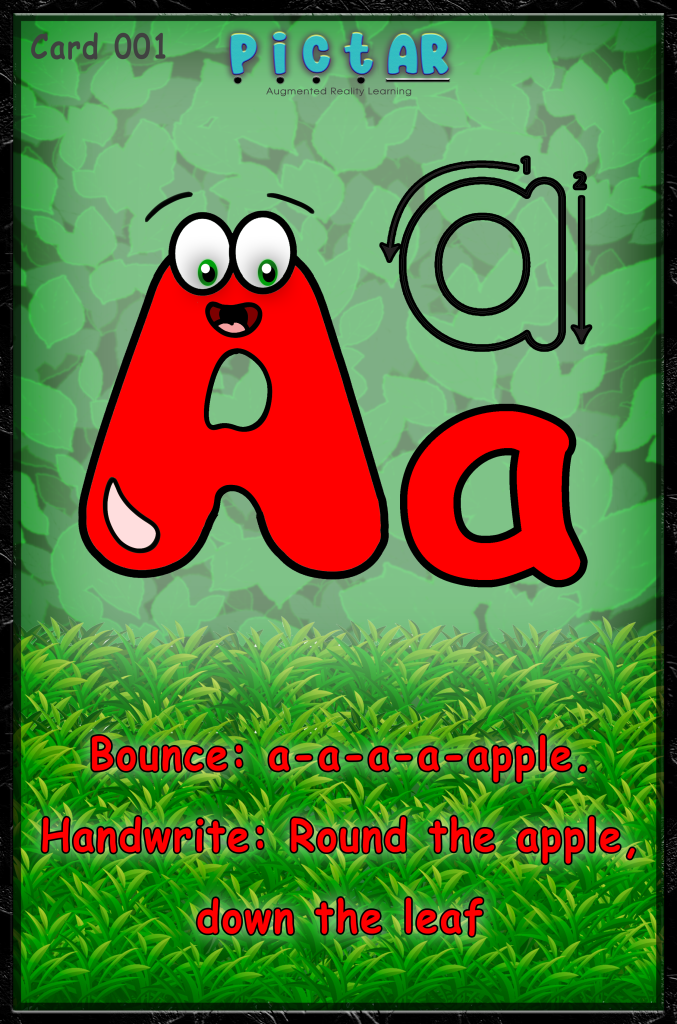

As mentioned previously in the proposal, education has become a hot spot for the use of new and emerging technologies. Many have researched the significant benefits to using Augmented Reality (AR) as a tool in order to support children in schools. The premise is that a school would subscribe to this proposed AR as a tool to support children either beginning their journey to learning through reading, or to support those who are having difficulties with grasping basic reading skills. The target audience for the piece, are schools with high need – those with increasing numbers of Special Educational Needs (SEN) children as well as English as an Additional Language Learners (EAL). A case study by Barquero et al. (2018) suggests that although many schools now follow a synthetic phonics approach to teaching reading, there are significant barriers particularly for the above-mentioned groups. The case study follows a girl with SEN who ‘is not able to decode all the letters of the words, cannot read with a speed that is not appropriate to her academic level and she does not write sentences independently’ (Barquero et al., 2018). The production piece was aimed at forming a solution for children like this. Imagine that this child has access to an engaging visual character who could mentor her through each finer step of the process. Imagine that there were cohesive lInks with a scheme of work, which the child can then follow through school. The piece begins with a card – with an image, a QR code and the linked character on the front. These cards would match the different single and joint sounds found in the Read, Write, Inc (RWI) scheme. Using whatever is available in the classroom (laptop or tablet) the child or a supporting adult could follow the link where they would then be taken to a site. When the site opens, the child is greeted by a fun and engaging character with direct links to the letter who would then – in real time – perform repetitive and supportive activities to help the child learn the letter or sound. The animation of the character would feel as if they were there in the classroom with the child and will model correct pronunciation, correct letter formation and forge links with possible uses to help the child form a deeper and more comprehensive understanding. The idea is formulated to support the growing need within the educational system. More children are using emerging technologies such as AR, and to advance, these developments need to be made within the education system.

As many schools use systematic phonics to teach children how to read and write correctly, this was a starting point for research for the AR. With a connection to a certain school in the area, this narrowed down the scheme to Read, Write, Inc scheme of learning. When researching this scheme, it became clear that there were five key components to ensuring the scheme was successful (Pace, Praise, Purpose, Participation and Passion). These components of success were used as a strong struvture when designing the AR software for the children. In order for the children to have the utmost success when using the AR software, the structure must run parallel with the themes of the scheme. Key points which were taken to use within the development of the AR were dynamic repetition, high expectation for development, easy to understand knowledge, little preparation necessary, clear modelling of sounds, encouragement to correct themselves with positive language and elevated levels of energy and enthusiasm to encourage engagement and participation from all.

When researching what type of character to use for the animation, it was imperative to look at the characters seen by children each day on television. The first character that stood out was a small berry from a Disney film which is colourful, ‘cute’ and has large engaging eyes. Chen and Zhunag (2023) found that ‘cute anthropomorphic characters evoke different feelings depending on their appearance and body proportion.’ This is where the focus was for design, a character needed to be created which was appealing for children to look at with proportions which were not too life-like. After producing a basic design, this was shown to a 5-year-old whose reaction was ‘he’s cute, I want to play with him.’ In Chen and Zhunag’s study (2023), five different image styles were found which linked explicitly with what children find ‘cute’. The character of the apple was therefore modelled around these image styles. These ‘cute’ character styles are ‘based on the identified design rationales of this study can be designed for diversity and inclusion in entertainment media’ (Chen and Zhunag, 2023).

In terms of animation, the character again needed to be childlike but with a supportive nature. Within the classroom, one of the teachers’ roles is supporting, affirming self-esteem, and using well-selected focused language. Many children associate self-esteem and success in school with academic success, however, for children who struggle in this area it is imperative to use supportive language to support perceptions of competence. By making the AR feel like it is not a normal lesson in reading and writing, children will feel less pressure, and with verbal support they will grow in self-esteem and thereby become more likely to develop skills of confidence and independence (Cosden, Elliot, Noble and Keleman, 1999.). This research supported animation of how the character speaks and the independent nature of the activity.

To complete the proposed idea at the pace expected, the set of principles, tools and techniques used to plan, execute, and manage the project have been based on different theories. The main project management style used when planning this project was agile project management. This was chosen to ensure the project could evolve to overcome difficulties through each phase of planning and creating. Due to the adaptive and evolutionary nature of this process, it allowed more creativity and room to improve ideas – all while keeping to a strict time expectation. When researching, it was found that this style is a more dynamic way to work and collate ideas in software development. In ‘Manifesto for Agile Software Development,’ (2001) which was authored by 17 different software developers, it mentions that this approach is perfect for ‘new and emerging software culture’ which is exactly what the nature of this project was. To ensure a level and structured direction for the project, eight essential milestones were followed. The first was gathering requirements. This step included ensuring a clear objective and scope for what was achievable with the timescale and limited access to certain technologies. During this stage, the concept was formed to create an educational based AR technology with a clear target audience. Next, was generating requirement expectations. In the previous proposal, the scope for the technology was too wide, therefore it was essential to minimise the goal in order to make it achievable (Smith, T., 2023). For the prototype, it is not fully interactable which was the preference in the beginning stages of planning. That, therefore, is a further way to develop the technology later down the line. It was important to keep the key features of the project, including likeable characters with basic functionality for a test basis. Through talking extensively with a school and teacher in the area who has expertise in this field, the project answered some key development questions in preliminary stages of planning. The application would be hosted as a physical to online feature with a completely new platform for learning. To use the Read, Write Inc(RWI) letter phonics, permissions would be needed as this would be a supporting supplementary learning resource to support a well-established scheme. The language and use of the AR would be age-appropriate and use language to reflect such. There were two main challenges to overcome within this project. The first was the coding ability.

To code a fully interactable AR, experience the level of coding was beyond the breadth of individual ability. So, to improve the user competence and functionality of the software, the end point was restricted. The premise was that the software would have more limited abilities but with higher functionality. Another difficulty for this type of software was ensuring that the target audience was catered for appropriately. As this needed to be targeted directly for children, particularly those with limited understanding, it was imperative that the characters, font, and usability were suitable for the target age range of between 3-11. This was difficult as, without education, it was hard to know if children would engage with the character and software. The created character was animated comparable to many popular children’s movies and television shows. When overcoming this, research was conducted at a local school where a class of 32 were shown the animation. The feedback was that 98% of the children would not only love to have an interactive learning experience when reading but would like to use this to support them at home. The teacher within the host school discussed necessary educational knowledge during the planning and development stages to ensure that the software was appropriate, engaging and school compatible. The theme of the apple came down to phonics cards already used within school, the font was also one used within the school that the children could read easily and were already familiar with. Another method for overcoming this was testing the software on a child at home (aged 5) and seeing what she likes and dislikes about it and improving it from there.

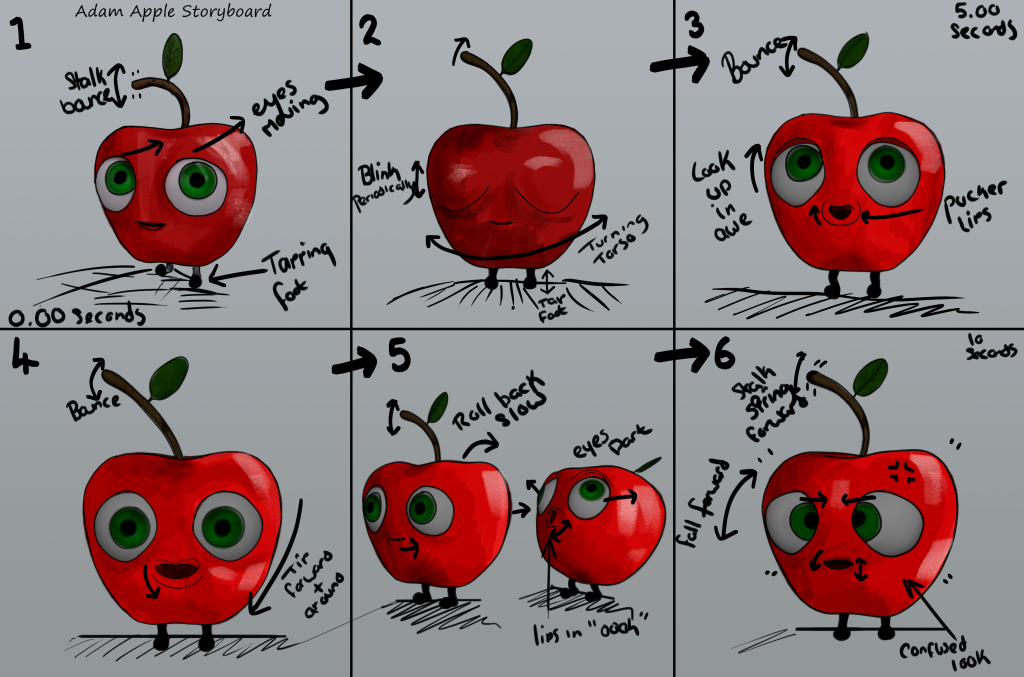

The use of Zbrush in this project was primarily for creating the actual model, its high. Through Zbrush a model was created from the examples in the mood board. It was modelled with cartoon-like features, like that of Pixar animations – with the primary inspiration coming from ‘Barry the berry’ from ‘Cloudy with a chance of meatballs.’ The sculpting aspect of this task came naturally however, due to the cartoon-like nature of the design, challenges were faced. Research was conducted and through modifying the design and simplifying the design, the model became more appealing to a children-based audience. Maya was used for creating the animation in this project, within Maya the character needed to be rigged and animated using key frames. A storyboard was created as a guide through the development process. The rigging and animation were not challenging within this task but, the export of the character to Unity did cause some issues. After watching some online videos, the information was compiled and luckily, a solution was found which allowed the character’s eyes to constrain the body. Topogun was used to retopologise the high model. There were no issues with this due to extensive experience using this. Rizom UV was used to UV the low-poly model before texturing, a minor issue surfaced with the eyes. During the texturing process, it was easier and more efficient to stack the eye UVs so they shared the same map. Substance painter was used to texture the model before importing it to Maya. Fortunately, no issues arose with this. Zapworks AR is used to host the Unity model and provide a website and QR to link to from devices – with a camera and an internet connection. Thanks to a previous tutorial hosted by Dan Wonnacott, the process ran smoothly and was able to be uploaded to Zapworks with little to no issues. Unity was used as the platform and engine used to create the AR experience. The animated model and animated experience were imported via Zapworks, this was supported by watching online tutorials and previous lectures. In addition to this, textures were able to be added.

Southgate et al. (2017) mentions that ‘the increasing availability of intensely immersive virtual, augmented and mixed reality experiences using head-mounted displays (HMD) has prompted deliberations about the ethical implications of using such technology to resolve technical issues and explore the complex cognitive, behavioral and social dynamics of human `virtuality’.’ As this project concerns children, it was important to take risks and ethical considerations seriously. When working on this project, the structure and elements included were created to make the game more appealing to children, for example the apple character. The three areas of pedagogy which were considered when formulating this AR experience were representational fidelity, learner interaction and an avatar which constitutes identity construction (Kaimara, Oikonomou and Deliyannis, 2010). Lee (2004) determined that ‘virtual objects are experienced as actual objects in sensory or non-sensory ways.’ The focus of this project was a sensory approach to engage children of an early age or those with learning difficulties. For children to understand that the project was interactive but not ‘real’, the representational fidelity was not human-like. This is so that children do not become overly reliant and understand that it is a tool for learning. This was supported with the cartoon-like animation of the character. Next, the consistency of the character’s behaviour has limited interaction – you cannot ask questions or conduct tasks which are unrelated to the specific needs of the AR (Dalgarno and Lee, 2010; Fowler, 2015). ‘Children’s engagement with immersive technologies is constantly increasing in all parts of the world’ (Southgate et al.,2017.). With this growing engagement, there are growing concerns, Southgate’s study found that using AR technology can have many detrimental effects for children, such as, cybersickness, obesity, sleep disorders, issues with attention and addiction. These became more prominent in the COVID-19 pandemic when children spent more time in front of computer screens. To tackle addiction, the game is only to be used for a maximum of 30 minutes per day, a parental/adult advisory would be issued. To tackle cybersickness, the children would have to be sitting at a desk and have limited use. Obesity in this case would not be an issue as the children would be using the AR only when they would normally be sitting at a desk studying at school. In terms of addiction, this is the hardest to combat. Children naturally want to be interacting with colourful, engaging activities – which this would be. As the target audience for the project is those with low attention in school, this would be considered a positive as it would engage children in areas they normally struggle with.

‘Over the last several years, AR applications have become portable and widely available on mobile devices. AR is becoming visible in our audio-visual media (e.g., news, entertainment, sports) and is beginning to enter other aspects of our lives (e.g., e-commerce, travel, marketing) in tangible and exciting ways.’ (Yuen, Yaoyuneyong and Johnson, 2011.) It is therefore conceivable that the next forefront for this technology would be education. AR can give learners ‘instant access to location-specific information’ (Yuen, Yaoyuneyong and Johnson, 2011.), which is precisely the necessary application for within education. According to schools and experts within the area, schools have growing funding for tablets and computers and children are the most excited about computing activities within school. The fonts used in the piece are engaging and link with the schools’ current standards and uses within the scheme of work. The character used is based on up-to-date cartoons and films with bright colours and big eyes, something the children will be used to. In recent years, there have been many more children identified to have additional needs such as dyslexia, the cards therefore come in different colours (basic, yellow, and pink) to allow diverse groups to access learning which in the past have not been considered. The software features three key components at the forefront of learning in reading: a clear letter, a rhyme to remember the sound and use of the letter and directions for letter formation. In the past, teachers would have to spend substantial amounts of time correcting letter formation as this is a growing struggle within schools, with this software, this will reduce a teacher’s workload, engage children who struggle and provide repetition – which is what is needed for children to excel. The use of AR in the classroom is an exciting prospect, in a local school a class of 32 voted on whether AR should be used in school, 99% of those children voted that it should be used in school and mentioned that ‘they would be excited about coming to school if school used features of the games which they use at home.’ (Tether, 2023).

References

Barquero, L. et al. (2018) CASE STUDY: READ, WRITE, INC. Bilingualism and children with difficulties. Published: Maestros bilingües y de Educación Especial (Pedagogía Terapéutica). [Accessed 3/1/24]

Beck, L. et al. (2001) ‘Manifesto for Agile Software Development’. Published online: 2001. [Accessed 1/1/24]

Chen, C. and Zhunag, X. (2023) The image ratios for designing cute nonhuman anthropomorphic characters. Entertainment Computing, Volume 47, August 2023, 100586 [Accessed 3/1/24]

Cosden, M., Elliott, K., Noble, S., and Kelemen, E. (1999). Self-Understanding and Self-Esteem in Children with Learning Disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22(4), 279-290. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511262 [Accessed 6/1/24]

Dalgarno, B. and Lee, M. (2010) What are the learning affordances of 3-D virtual environments? Br J Educ Technol 41:10–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01038.x [Accessed 30/12/23]

Fowler, C. (2015) Virtual reality and learning: where is the pedagogy? Br J Educ Technol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12135 [Accessed 1/1/24]

Kaimara, P., Oikonomou, A. & Deliyannis, I. (2010) Could virtual reality applications pose real risks to children and adolescents? A systematic review of ethical issues and concerns. Virtual Reality 26, 697–735 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-021-00563-w [Accessed 4/1/24]

Lee, K. (2004) Presence, explicated. Commun Theory 14:27–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00302.x [Accessed 2/1/24]

Southgate, E., Smith, S. P. and Scevak, J. (2017) “Asking ethical questions in research using immersive virtual and augmented reality technologies with children and youth,” 2017 IEEE Virtual Reality (VR), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017, pp. 12-18, doi: 10.1109/VR.2017.7892226. [Accessed 10/1/24]

Smith, T. (2023) 8 Essential Milestones to software development. Published online: 2023. [Accessed 2/1/24]

Tether, M. (2023) A study into using AR in the classroom. Conducted with year 5 and 6 at Paisley Primary School, Hull.

Yuen, S. C., Yaoyuneyong, G., and Johnson, E. (2011). Augmented Reality: An Overview and Five Directions for AR in Education. Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange (JETDE), 4(1). https://doi.org/10.18785/jetde.0401.10 [Accessed 4/1/24]